In our last thinkpiece “Engaging with citizens in a post-pandemic world” we looked at how the coronavirus pandemic is, and will need to, change the way in which we engage and consult with citizens, and the importance of urban stakeholders documenting and sharing experiences and lessons learned with the wider global urbanism community.

Another consequence of the pandemic – and the increasing realisation that coronavirus is here to stay with us for the foreseeable future – is how it is affecting the way we will need to use spaces in our cities: not just offices, streets, public buildings, but our homes too.

The home environment

I referenced emerging reports about the effect of coronavirus quarantines or ‘lockdowns’ on mental health in my first blog. We have known for many years that our living environments can significantly impact upon our well-being, and the pandemic has underlined this in a brutally clear way. Multiple studies are now emerging demonstrate that access to safe outdoor space being a critical factor in the health and well-being of all demographics, including children. In the UK research by the Resolution Foundation discovered that those already experience “living inequalities” – ie. poor build quality, overcrowding, little or no access to safe outside space, areas of high crime and/or anti-social behaviour – suffered disproportionately high negative impact on their mental health and sense of well-being, and that it was the under-18 and over-65 demographics who were most over-represented in this suffering. On the flipside, a study of extra care residential developments for the over-60s in the UK found that balconies had emerged as being critical safe spaces during lockdown, enabling physical distancing to be maintained whilst also allowing communal activities and communication to be maintained.

Our experience of Covid-19 will change the way many countries need to design and build our homes from now on. And that includes recognition of the increasing number of non-related multi-adult households (eg. flat-shares, etc). Although access to private safe external spaces – even if only micro-spaces in the form of balconies, roof gardens, etc – is important but not the only re-think needed. I have already talked about the physical and mental-health perils of extended spells of home-working in unsuitable set-ups in an earlier blog. Residential designers now need to consider how they can create homes that can accommodate 1 or more adults in each household having suitable private space for working from home for extended periods, through improved space standards, or flexible fixed design with multi-purpose spaces a core design building block. Australian design practice Woods Bagot is even re-thinking the home in terms of modular building systems, whereby both internal and external walls of homes can be moved on an hour-by-hour basis to adapt to the changing needs of its occupiers throughout the day or week. For those who already have the luxury of external non-habited space, separate ‘locked-off’ office spaces may emerge, for example this sunken garden office. The more recent trend for integrated kitchen + living spaces – especially in apartments – may also need to be re-thought, as many have found that that the noise and/or odour they create a major distraction from home-working.

Multi-unit buildings, with up to hundreds of resident households, will need to find a way of making essential communal spaces – entrance lobbies, lifts, corridors, bike stores, laundry rooms, etc – safe and secure for multiple entries & exists by multiple users. The dimensions of these spaces now may need to become more generous to allow safe physical distancing. Multi-unit residential buildings may also need to consider having a greater number of entrances & exits per building unit, or even the provision of more single-use individual apartment entrances. New ‘transitional spaces’, where people movement can be controlled and sanitised, are likely to become a fundamental component of not just residential blocks, but office blocks and restaurants too.

And all of the above is only for new developments: another challenge will be how to retro-fit existing buildings. One Spanish city that I work with is reviewing the feasibility of a model whereby 1 or 2 whole floor of apartments in the central floors of a 1960s multi-apartment high-rise residential block can be removed to create an internal ‘garden’ space for use by residents.

In tandem with the above there needs to be considerable investment in digital infrastructure to facilitate home-working. I’m sure I am not the only professional who has at times been on the verge of tearing their hair out at sub-par network speeds, bandwidths and network outages! Those cities and regions already rolling out 5G technology will find themselves at a distinct advantage; on the corollary, those in more rural areas may find themselves even more disconnected from work opportunities.

Offices

With ongoing concerns about the ability to make large office buildings 100% safe for users many companies have decided to maintain ‘work-from-home’ as a policy, or as a voluntary option, for their staff. Anecdotal evidence from many has been that home-working has, despite the many practical challenges of the home environment as set out above, has improved their quality of life: in my social media timelines almost no-one is missing their crowded, unpleasant and expensive daily commutes, and almost all are savouring the additional time saved on those commutes.

Many are starting to fundamentally question the future role of “the office”. Some question whether there is a future for large open-plan offices at all – with some likening them to ‘cruise ships for their potential to spread the virus’. Others think office spaces should now switch to being a place that workers occasionally visit for meetings and essential large gatherings, but do the majority of their focused work at home, with the former being facilitated by a small number of temporary ‘pop-up’ installations configurable within the existing large floorplate. The future of ‘hot-desking’ offices – where no-one has a permanent desk and the number of desks is less than the number of office staff – is also under question. I know from my time working in such an office – where there were only hot-desking spaces for 65% of the employees based at that office – that they were difficult to keep sanitary back then, and that was well before the new physically-distanced anti-viral Covid-19 world we now find ourselves in! I personally felt they didn’t promote a healthy collegiate working environment either – an experience underpinned by one unnamed global consultancy firm whom confessed they had quietly removed 80% of its new hot-desking offices less than a year after opening (pre-pandemic) when they discovered productivity had dropped by 23%. In a similar vein, the future of dedicated co-working spaces – which grew hugely in Europe and the US in the past decade on the back of offering a busy hive-like atmosphere and social interaction with like-minded entrepreneurs – is now similarly under question.

Recent surveys of heads of real estates – such as this by CBRE – across many organisations globally suggest that the pandemic *is* triggering rapid significant strategic change in terms of property portfolios and the structure of how ‘work’ is delivered; but that innovation is likely to be seen in terms of team-building and informal staff development, both of which are tricky to achieve via remote office-working.

There are knock-implications of the way the pandemic has affected the pre-pandemic models of office-working, already being felt by real estate investors who have immense amounts of capital – literally billions – tied up in prime city real estate; for those who provide associated services, such as takeaway food, cleaning, security, etc, who are making significant job cuts in response to the huge drop in demand. Investment values have declined sharply in the first half of 2020, with ongoing uncertainty about the second half of the year. The UK RICS’ Global Commercial Property Monitor concluded in August 2020 that “property values are likely to remain under some pressure even with the cost of money at rock-bottom levels”. It is likely that there is simply too much capital tied up globally in existing office space to see their use entirely swept away, but I predict that for the next 12-24 months we will see radical reinvention of how they are used.

Enclosed Public Spaces

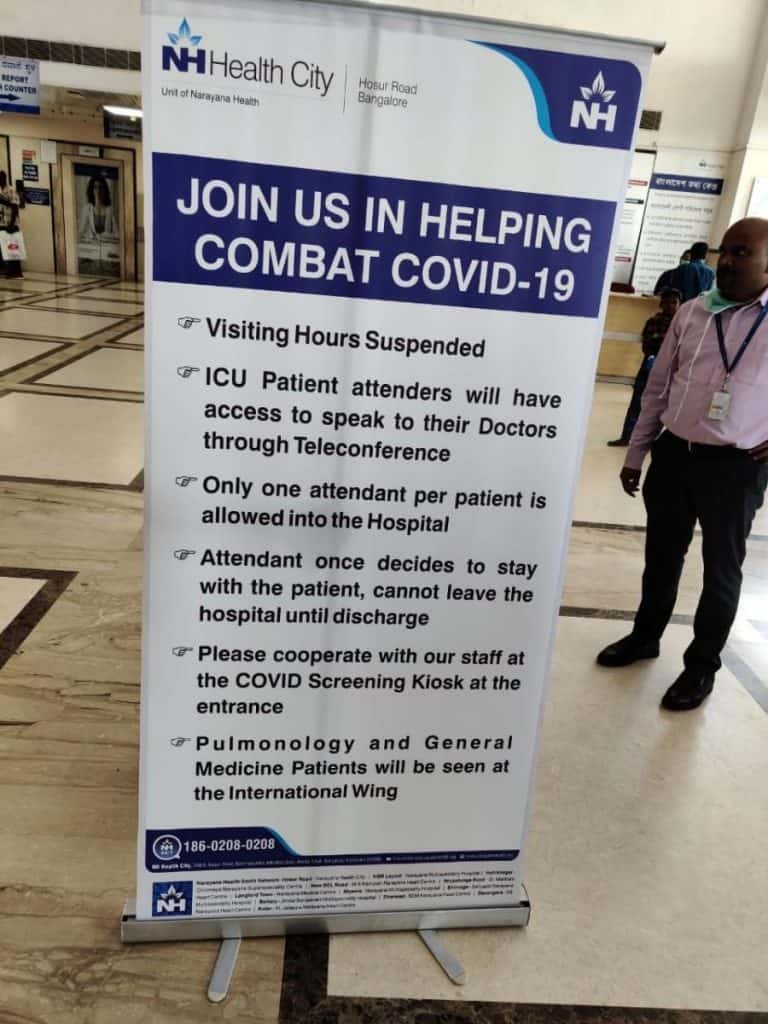

A whole range of publicly-accessible buildings have had to contend with re-designing how the public access and use their fixed spaces. At the outbreak of the pandemic many closed their doors to the public completely, and switched to delivering services online, including schools, town halls, public agencies, libraries, etc. Some, such as hospitals and schools in some countries, were restricted to essential users-only.

As more was learned about the risks of Covid-19, some buildings were able to accommodate re-opening albeit with strict conditions: some re-deployed staff to restrict the number of people entering – and hence circulating in – the building; some countries have now switched to an appointment-only access system. Almost all have made wearing of masks a condition of entry, and deployed mandatory supplies of antiviral hand gel for use on hands, and in shops, baskets & trollies; spacing requirements and one-way systems, designed to minimise contact between arriving customers and departing customers, were put in place in many public buildings.

So far, whilst there have been service delivery challenges, existing public buildings seem to have adapted well to the ‘new normal’. However how sustainable this is in the long-term – in particular if service delivery constrictions lead to an unsustainable backlog – remains to be seen.

Public open space

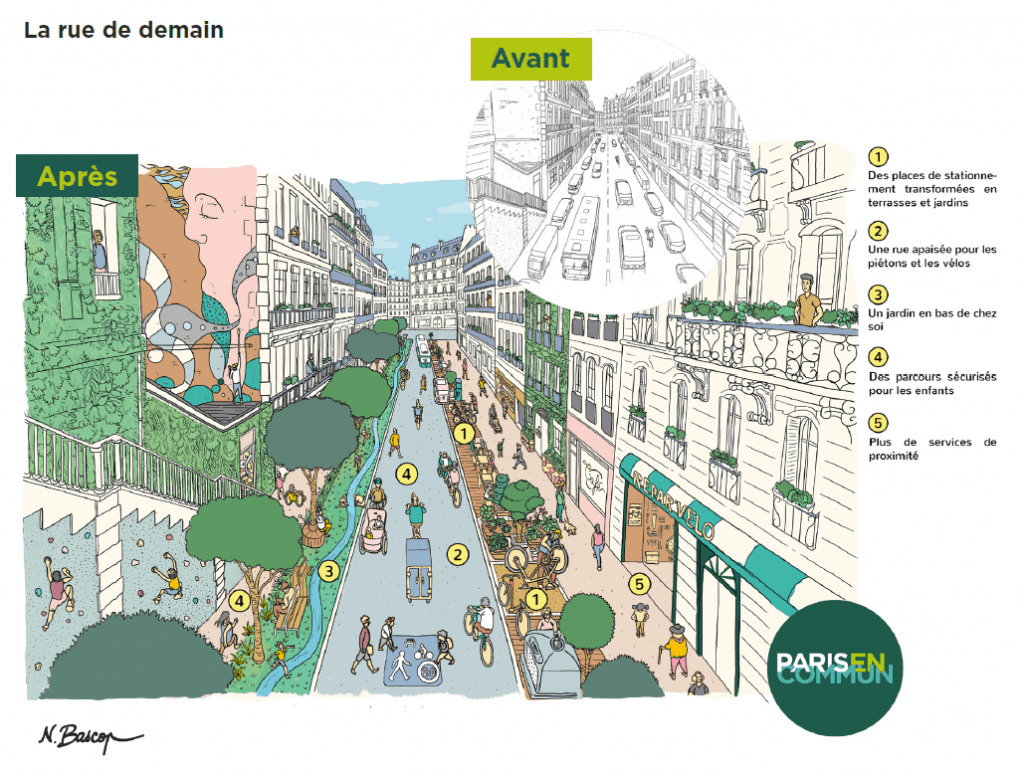

In my first blog about the new coronavirus world in May there had already been calls from some cities, such as Milan, for ideas “to find solutions capable of reconciling security and social distancing with needs for socialising and conviviality of people and for the use of shops and services”. Cities such as Paris, with its manifesto for “La ville au ¼ heure”; Singapore, with its plans to secure food supplies via urban rooftop farming; and Nantes, with its existing award-winning network of neighbourhood green spaces, were already ahead of the game even before the pandemic struck.

Shortly after this came a more comprehensive re-think of the design and organisation of key public spaces: for example, Scott Elliott Adams and Chris Martin (no, not the one from Coldplay) developed on behalf of the Urban Design Group (UDG) the “Life-Saving Streets” manifesto (disclaimer: I am a member of UDG), which looked at retail-led mixed-use streets, residential-led community streets, parks and landmark destinations and interim solutions for their design and accessibility. In the US the Bloomberg-supported National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) “Streets for Pandemic response, and Recovery”, which provides a series of guidelines which act as a blueprint for a variety of uses of streets, in response to a “… pandemic (which) has laid bare and amplified structural inequities and pre-existing socioeconomic disparities across communities…. This (set of guidelines) looks to make it easier for cities everywhere to respond faster, innovate better, and support their residents in more equitable and sustainable ways”. Others, such as New South Wales (NSW) Government in Australia, launched major programmes to re-purpose existing streets to create more space for communities to safely walk and exercise: their “Streets as Shared Spaces” being a US$15m rapid injection to achieve this objective.

One other impact of Covid-19 on public open spaces in cities was their adaptability in being used to create emergency field hospitals in cities like New York during the peak of the pandemic – in many ways the opposite benefit to those perceived by many.

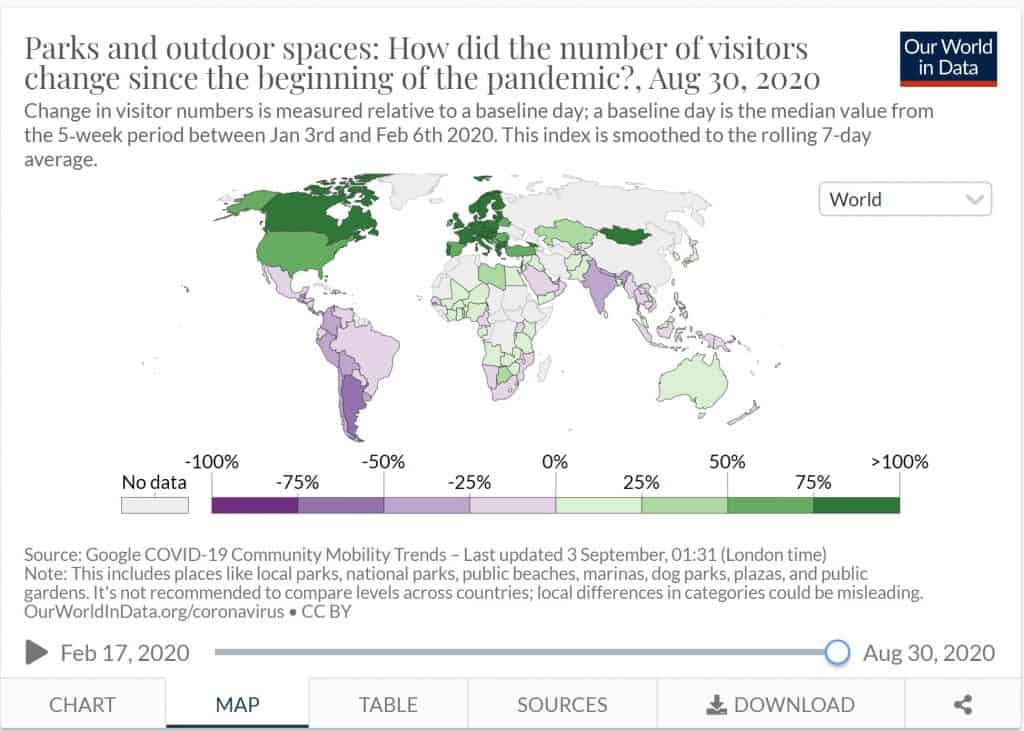

Usage of public open space in general has significantly increased during the pandemic lockdown: a website operated by ourworldindate.org is tracking usage in real time, which has to date seen a net increase in greenspace usage in much of the Northern Hemisphere, Australia and parts of Africa (whereas usage in South America and the other half of Africa has declined). Over-use of these spaces has become an issue in some parts of the world. How designers might be able to deal with this, either with retrospective re-design or innovation in new design, has yet to be established.

Conclusion

It is now clear that we will all have to learn to co-exist with Covid-19 in the short-term, and – subject to availability and effectiveness of vaccines – possibly into the medium-term too. This has inevitable consequences for the way we use existing space in our towns & cities, and how we design future spaces. As we can see above, the story in respect pf physical spaces is still writing itself…. so how it all ends will literally be a case of “watch this space”.

But one key point to remember is that cities are not preordained: cites are the result of specific decisions made about public space. The significant increase in use of greenspace during and post-lockdowns has reinforced their value to many in society as a valued place for exercise and socialisation: it is for urban planners to ensure that they are now used as a key tool in re-building communities in the new post-pandemic world.